Work Camps

Internment Work Camps in Eagle Pass

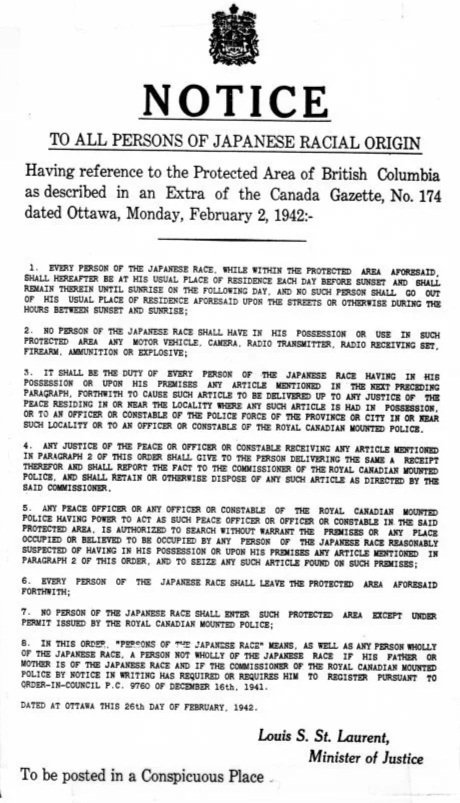

When war was declared between Canada and Japan, the original intention by the federal government was to remove only Japanese National males between the ages of 17 to 45 from the British Columbia coast and place them in work camps in BC.

Nikkei National Museum, Sunahara Collection, 2018.16.3.1.2.

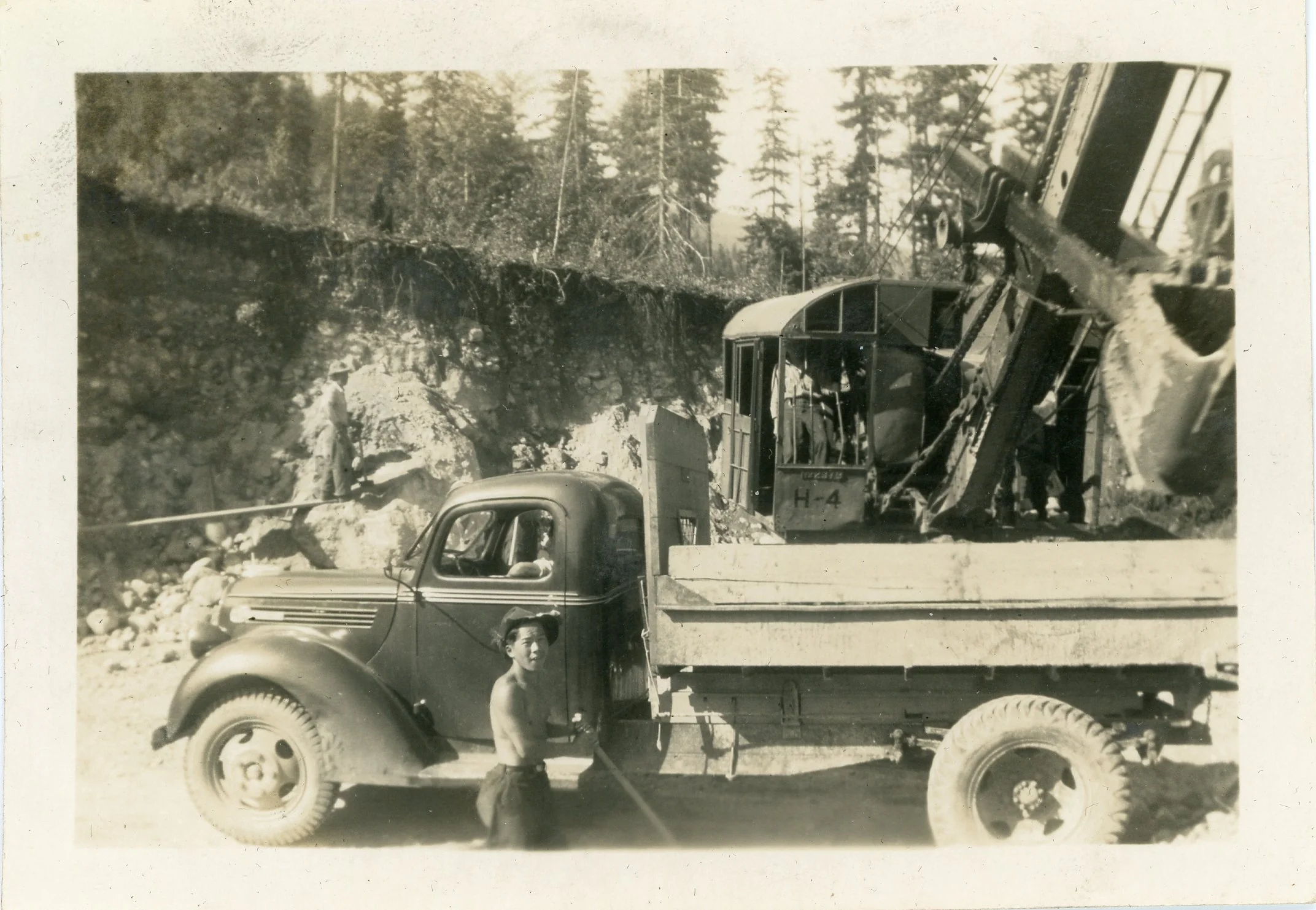

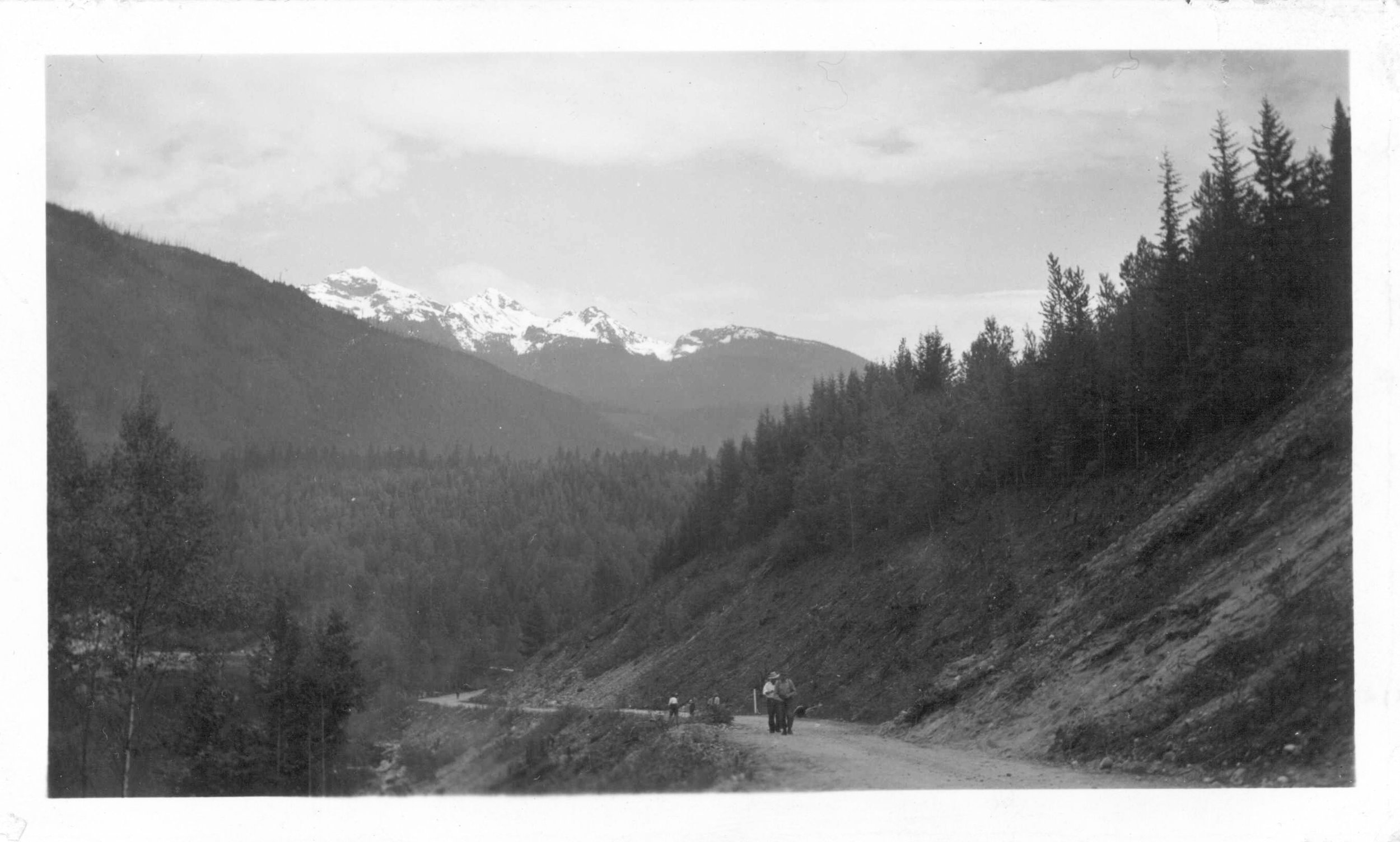

On February 26, 1942, a Total Removal Policy was announced, forcing all of the Japanese Canadians living on the BC coast to be removed outside of a 100-mile zone. As well as the internment camps established in the interior of BC, the government decided to place men in designated work camps in the province. Government correspondence showed that the project to widen and improve the highway between Revelstoke and Sicamous was number three on the list of preferred projects. Some concern was expressed regarding potential sabotage to the main CPR line that paralleled the road, but it was felt that the risk was minimal.

The chief justification for the camps was to quickly absorb 500 to 600 Japanese Canadian men. The road camps were considered a temporary expedient, with limited value from a National Defence standpoint. It was determined that if more men were needed on other projects, they would be drawn from the Eagle Pass camps.

Three Valley Camp garden, ca. 1943. P-12745.

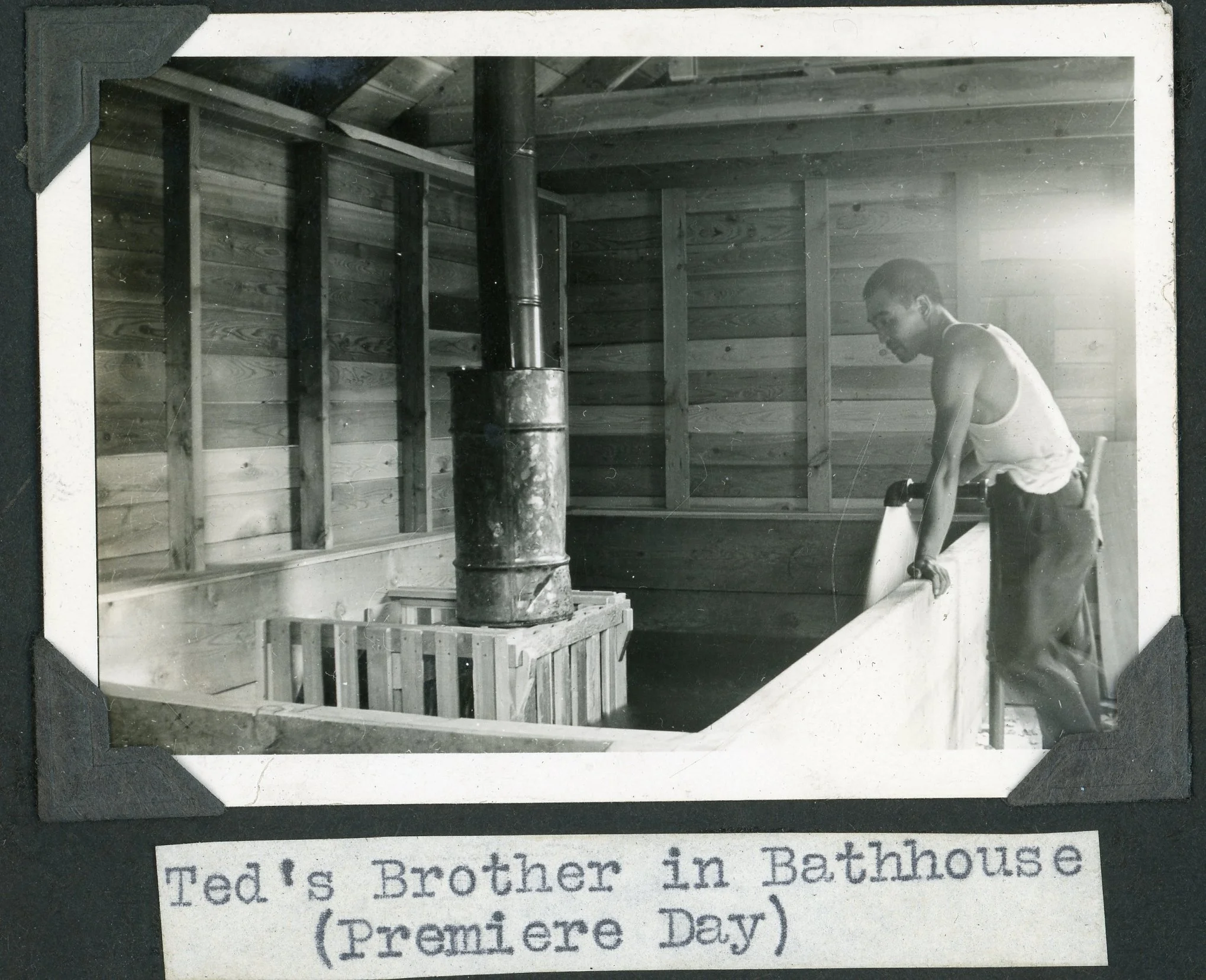

The men were to be paid 25 cents per hour for eight-hour days. They would be required to pay for their own meals in the camp mess halls, and to supply their own blankets and clothing. The officials in charge of the camp expected that the men could net $33/month. The government promised to pay $20 per month to dependents, plus a smaller amount per child, up to five children.

Camps were opened in 1942 at Solsqua, Cambie, Yard Creek, Griffin Lake, Taft and Three Valley, all located between Revelstoke and Sicamous, with another camp at Mara Lake, just west of Sicamous.

An article in the April 16, 1942 edition of the Revelstoke Review paints an overly positive view of the camps, but also points out how beneficial the camps were to the economy of Revelstoke and to local businesses:

“Japanese Road Crews Filling Up: During the week Japanese have been arriving from the coast to fill up the camps on the West Road. Outfit cars are parked on the siding at Three Valley, Taft, Cambie and Solsqua. Carpenter gangs are busily engaged in erecting camps on the highway which will be occupied shortly by the Japanese, in addition to the camps above mentioned also to be established at Griffin Lake and on Mara Lake. Each of the outfit cars is under guard by special constables of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. A large number of local men have found employment as cooks, timekeepers and in other capacities. The foremen are local men as well. The Japanese are young men and appear to be quite pleased with their lot. Members of a road gang which arrived Tuesday were in Revelstoke that afternoon buying personal requirements at local stores. Hon. R.W. Bruhn, Minister of Public Works, is expected to make an inspection of the camps shortly.”

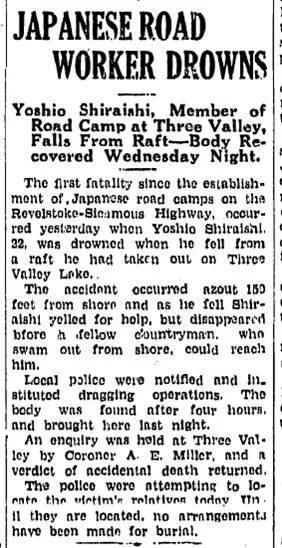

In great contrast to this rosy view was an article in the same issue with this headline:

Death of Yoshio Shiraishi article from The Revelstoke Review, April 16, 1942.

“Japanese Road Worker Drowns. Yoshio Shiraishi, member of road camp at Three Valley, falls from Raft – Body recovered Wednesday night.”

“The first fatality since the establishment of Japanese road camps on the Revelstoke-Sicamous Highway occurred yesterday when Yoshio Shiraishi, 22, was drowned when he fell from a raft he had taken out on Three Valley Lake. The accident occurred about 150 feet from shore and as he fell Shiraishi yelled for help, but disappeared before a fellow countryman, who swam out from shore, could reach him. Local police were notified and instituted dragging operations. The body was found after four hours and brought here (Revelstoke) last night. An enquiry was held by Coroner A.E Miller, and a verdict of accidental death returned. The police were attempting to locate the victim’s relatives today.”

Revelstoke City Council had passed a resolution that all applications from Japanese Canadian families wishing to settle in Revelstoke be refused. Two aldermen tried to make an amendment that Japanese residents already living here be allowed to bring their families, but this amendment did not pass. Some families settled outside of the City Limits, which at that time did not include Big Eddy, or land south of Downie Street.

In May of 1942, City Council was informed that their resolution opposing the presence of Japanese Canadians within the city limits was being construed to mean that Japanese were unwelcome in the city at any time. The council wished to allow Japanese men in the work camps the opportunity to do business in Revelstoke, and stated that Revelstoke merchants should have the opportunity to benefit from the purchases which the workers would make. A resolution was passed instructing the city clerk to write the BC Security Commission asking that the Japanese Canadians in the road camps be permitted to come to Revelstoke to make necessary purchases. There was a suggestion that they be allocated specific days to come to town, and this was put in place.

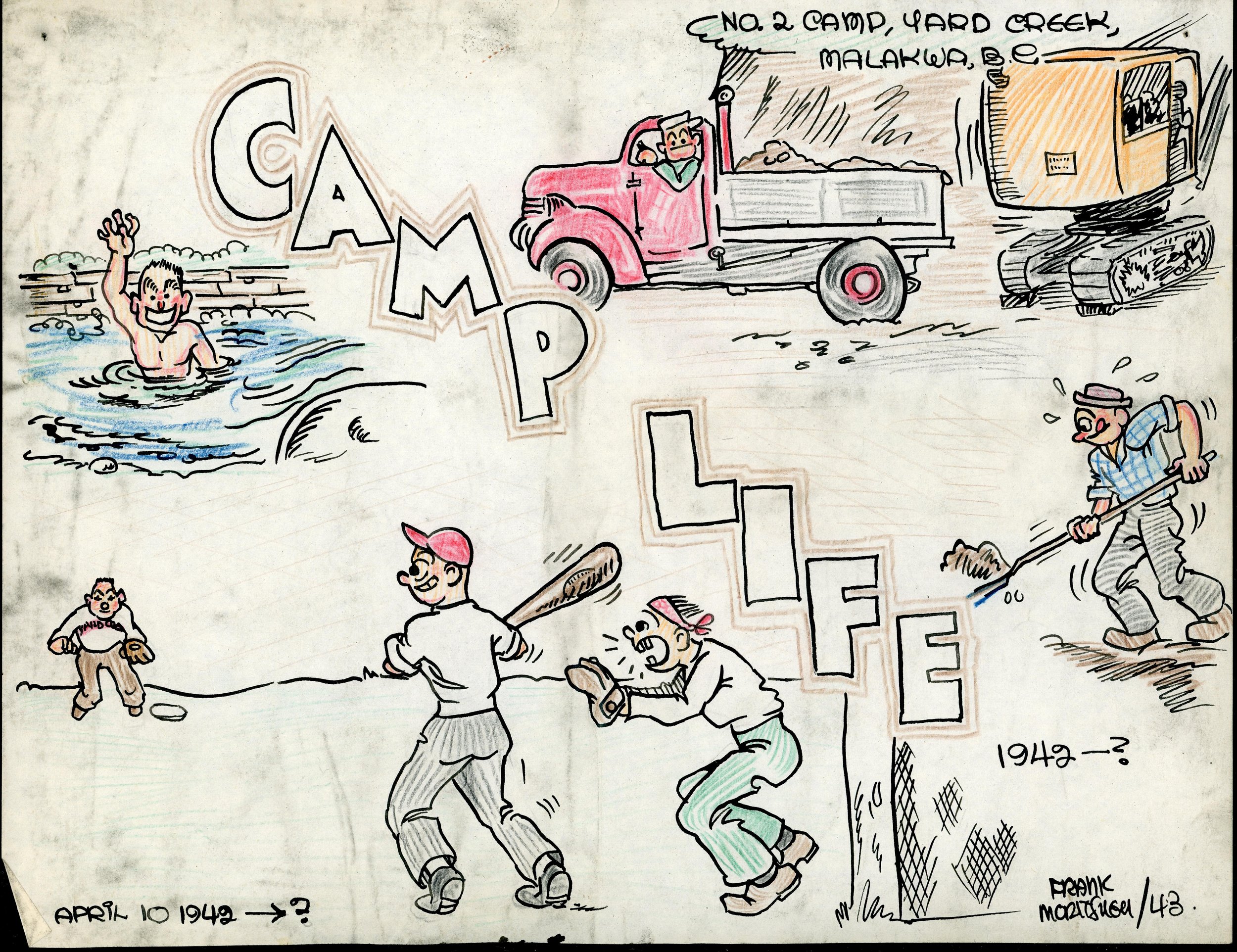

In July, Frank Moritsugu, at Yard Creek camp, writing in The New Canadian newspaper, (a Japanese Canadian newspaper published at Kaslo) said, “The camps around here each have a certain day when members are allowed to visit Revelstoke and as our day is Saturday it is said that we are the envy of the other camps.” That was because they could go to the Saturday matinee at the Avolie Theatre.

Letters and reports to The New Canadian newspaper gave a glimpse into life in the camps. Robert Oikawa wrote about life in the Griffin Lake camp in the July 4, 1942 edition:

“At present there are fifty-one of us in camp here ranging in age from 16 to 58. Fourteen are naturalized Canadians and the rest are Canadian-born. Each week twelve of us are allowed to visit Revelstoke, where we are well received. We are permitted to stay and take in a show. Several families are residing there. On the evening of June 27, a shin-boku-kai or social event was held. The foreman, staff and guards were invited. Highlight of the evening’s entertainment were musicals and solos.

Work at this camp consists of clearing brush and trees along the proposed right of way, some unfinished work of clearing and building around the camp, and everyday chores.”

Also in the July 4, 1942 edition, Frank Moritsugu complained about the mosquitoes at the Yard Creek Camp with this alliterative headline:

Cartoon by Frank Moritsugu, 1943.

“Malakwa Mauls Many Murderous Mosquitoes”

“Brushing aside swarms of mosquitoes which are of a very bloodthirsty variety, this correspondent will try to give you belated news of what’s happening at the No. 2 Camp at Yard Creek.

Most of us have never seen or rather felt so big and so many mosquitoes as they have here. Mosquito nets, ointments and mosquito repellents are being bought in such amounts that the storekeeper at Malakwa should be able to retire soon if this mosquito epidemic keeps up.

On Sundays we have the one thing that keeps us going. That is the weekly baseball game with Solsqua, the nearest camp (over 7 miles away) at the Cambie ball-grounds.”

By July of 1942, it was reported in a letter to the Revelstoke Board of Trade that there were 500 Canadian-born and naturalized citizens in seven camps.

Henry Popplewell, secretary of the Farmers’ Institute reported in February of 1943 that 77 tons of vegetables had been sold to the camps by farms in Revelstoke and district. This one was of many articles in the local newspaper that made it clear that locals were benefitting financially from the camps.

Internees at Yard Creek, August 1943.

This view was born out by a reported rumour that the work camps were to be closed and that the Japanese Canadian men forced to work on road construction were to be moved to the prairies and Ontario to work on sugar beet farms. An editorial in the February 24, 1943 issue of the Revelstoke Review expressed concerns about the economic impact to the city:

“The local Board of Trade, which was instrumental in having the camps located in this vicinity, can be relied on to do everything possible to have the camps remain on the West Road. Not only has the project meant a great deal to Revelstoke at the present time, but it will represent still more when tourist travel is resumed and the Revelstoke-Sicamous Highway is in a suitable condition for tourist traffic.”

Civil Engineer N.E. Willett, who was in charge of the project, stated in June of 1943 that there will still 250 men in the various work camps between Revelstoke and Sicamous. He expressed satisfaction with the work: “The project has meant a great deal to Revelstoke people, who have found employment in key positions as well as to the business life of the community.”

The August 5, 1943 issue of the New Canadian commented on a report in House of Commons by Minister Crerar that the Japanese Canadian workers on the Hope-Princeton Highway were not doing as much work as might be expected from them.

The New Canadian commented that if the complaint was true, it could be tied to the wage of 25 cents an hour, out of which is taken 75 cents per day for food, lodging and $1 per month for medical.

“For 18 months, these men have been cut off from all normal society, isolated in the rudest of lonely wilderness camps, engaged in work of no immediate national or wartime need. Their wages are a third of what many civilian war workers in the country today do not hesitate to strike over.”

Internees in Revelstoke on day off, 1942.

By late 1943, many of the men had been sent to other work projects in BC, on the prairies, and in Ontario. The camps in Eagle Valley were reduced to three, at Yard Creek, Griffin Lake, and Taft.

On New Year’s Eve, 1943, 20-year-old Noboru Amano died when the truck he was driving plunged into Three Valley Lake. The three passengers, non-Japanese Revelstoke residents, survived. Amano lived in town with his parents on Downie Street, and was returning home in the Davidson’s Transfer work truck.

In June of 1944 it was noted that the Revelstoke-Sicamous Highway had been extensively improved, and there were fewer than 50 Japanese Canadian men left in the camps. They were all closed by July.

The view from the community was that the project had been successful. The highway was improved, and local businesses and workers benefited economically. Few in the community would have seen the toll that this project took on the men who were forced to work in the camps. The vast majority of the men were young adult Canadians whose parents had been born in Japan and came to Canada to provide a good life for their families. Many of these young men would have been going off to university, starting careers and families, or even signing up to fight for Canada, the country of their birth. Instead, they were forced to do hard physical work for meagre pay, and were separated from their families, who were already dealing with the struggles of internment.