The Impact of World War I on Revelstoke

By Ken English

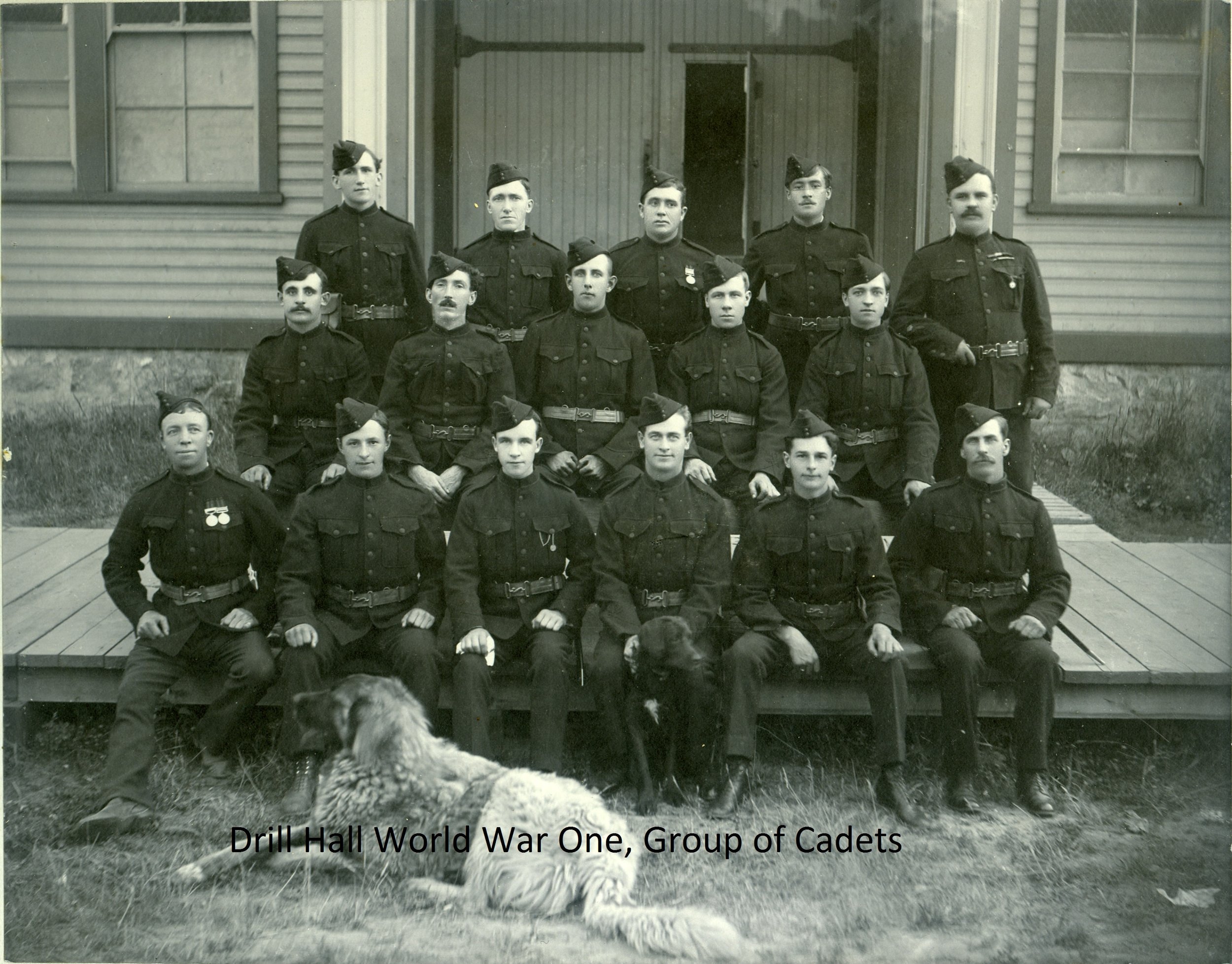

Dawn’s early morning rays stream across the sky. Its warming rays illuminate the south east stone surface of the Revelstoke Courthouse, exposing to its light a bronze plaque upon which names of those long departed are engraved. For those of us who live in peace dawn is a time of renewal, a time to begin again our daily tasks. For the soldiers of the Great War, dawn was the time for the beginning of battle. The coming of the dawn was a time of apprehension, of worry, of fear, for many knew that this could be their last day on earth, the last day they would greet the coming of the renewal of life. The poets of the Great War used the contrast between the dawn they knew before the war and the dawn they experienced in the trenches as a means of illustrating the contrast from the high idealism and confidence that guided their lives before the War and the new reality of the brutal, industrialized, mechanized world of death they now inhabited. Their noble war had become a war of attrition where millions eventually lay dead on the battlefields, many thousands never to be found again and remembered only by memorials.

This experience led to the downfall of previously powerful empires and also redrew the boundaries of the Middle East, the effects of which we are still experiencing today. Many historians believe this war may also have laid the groundwork for an even more destructive war to follow. It profoundly reshaped Western European culture and has shaped the Canada we live in today.

Our nation was forged in the fiery furnace that was World War One. It was forged in the Battles of Ypres, the Somme, Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele and the final 100 days. The Great War also had an enormous impact on the city of Revelstoke and affected every aspect of daily life. The Revelstoke Museum and Archives has compiled a Memorial Book with a one page summary dedicated to each soldier who died in this conflict. In this way we hope to throw some light on this change and to remember the sacrifice of these men and the effect this loss had upon the families and friends they left behind.

Cathy and I did quite a bit of research – primarily through the Museum and Archives collections which included the local newspapers of the time and through the Internet, on the impact the First World War had upon the community of Revelstoke. Its greatest effect of course was the loss of life from our community. Around 100 men from this area lost their lives in that conflict. Probably two to three times as many returned from the war wounded in body and/or spirit. I estimate that between 800 and 1000 men from this area served in that conflict.

What was it like for a community of the size of Revelstoke with its population of around 3,000 people within its city limits and another 3,000 in small communities along the CPR line east and west of Revelstoke and farming and logging and mining communities north and south of town to lose so many young men from its midst? At one point the newspaper mentioned that 20% of the male population of Revelstoke had volunteered to serve. The vast majority of our young men no longer worked or resided here. The loss of all these young men from our community would have a significant effect upon the economic and social life of Revelstoke.

At the initial outset of the war there was great enthusiasm and patriotic fervor in Revelstoke. Canada, of course, as a member of the British Empire, was automatically at war when Britain declared war against Germany. This was to be a war that would stop German militarism and defend the values of the British Empire from German tyranny. At least those were the reasons given to the public. The actual causes of the war are much more complex but basically boil down to a struggle for the balance of power between the major European countries; Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia. In those years the call of the British Empire for help defending itself from the evils of German militarism was very strong in English Canada and Revelstoke was willing and eager to do its “bit.”

An important question for me is what motivated all these men to join up and go off to fight. I had always viewed the First World War as one great useless slaughter carried out by incompetent generals. Who willingly goes over the top from the trenches to an almost certain death? Through my research I have now come to appreciate why these men volunteered to fight for a cause they believed in and why they carried on through so much slaughter and carnage. It also gave me some insight into why most of the people of English Canada supported the prosecution of the war to its end.

This story of the history of the Great War in Revelstoke has two parts to it. One is the story of the men (and some nurses) from Revelstoke who served at the front. The other story is that of the families and friends and fellow citizens of Revelstoke they left behind. Both stories are essential to our understanding of how Canada (and Revelstoke) became the societies they are now.

Engraved on the plaque at the cenotaph are some 93 names of Revelstoke men who perished during and after the First World War. Before our research I knew next to nothing about these men. Now I can pick out almost any name on that plaque and know something about that person. I now think what a privilege it is for me to be able to do that. Then I thought how important it is that somehow we all remember who these men were. They were just ordinary Revelstoke men living through extraordinary times. They answered the call to serve their country and the values they believed it represented. They did not return to share in the benefits our land can offer. The people of Revelstoke endured days such as June 3, 1916 when six Revelstoke men died at the battle of Mount Sorrel and April 9, 1917 when twelve men from Revelstoke died at Vimy Ridge. Another seven men died at Passchendaele in October/November 1917. Indeed the cost in men from Revelstoke was high.

One item I wish to emphasize is the tragic fact of war that many of the battle dead are never found or identified. Although about ¾ of the Revelstoke casualties are buried in identified graves in France and Belgium; about ¼ of the Revelstoke casualties (or about 25 men) bodies were not found or identified and are memorialized on either the Menin Gate (Ypres) Memorial or the Vimy Memorial both in France. Only three are buried in Revelstoke and one in Arrowhead. Another noteworthy fact is that ½ of the Revelstoke casualties occurred before the battle for Vimy Ridge in April of 1917 and ½ died after this battle to the end of the war in 1918 and beyond. A number of men died after the war from wounds, the effects of living in the filth of the trenches or from being gassed. Many of those who perished still have relatives living in Revelstoke. Then after the war influenza struck the world. Another 35 residents of Revelstoke died from this outbreak – possibly a result of weakened immune systems caused by the deprivations of the war years.

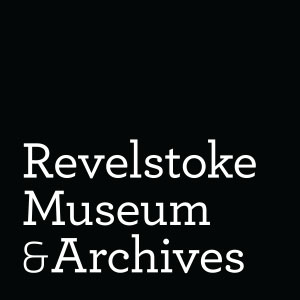

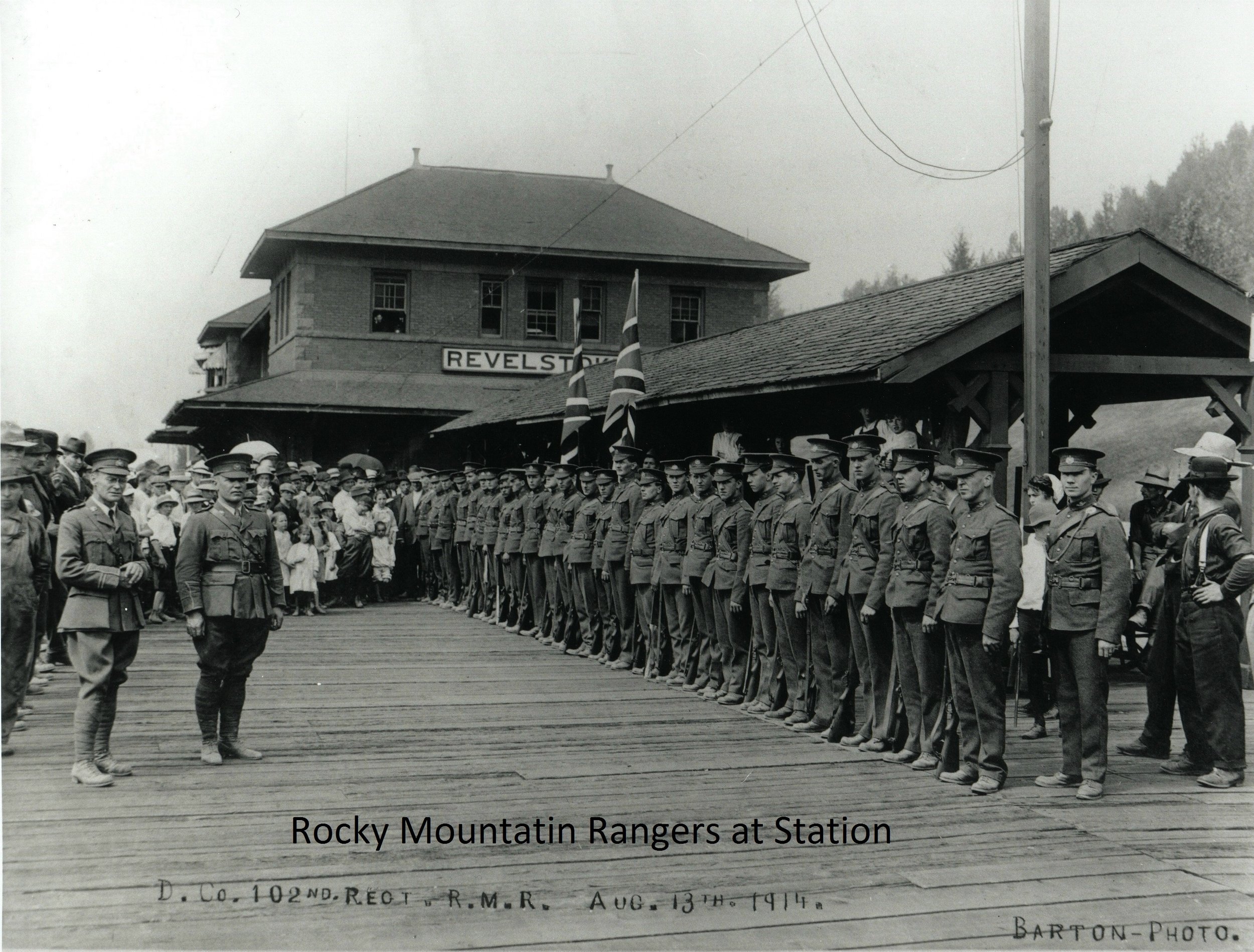

The real beginning for the First World War for Revelstoke begins in 1899 with the Anglo-Boer War in South Africa. Canada sent over what one historian called “our splendid little army in the field” to assist the British. Apparently it acquitted itself well; so well that its success led to an outgrowth of militia fever across English Canada. Drill Halls were built in many large and small communities across Canada, including ours. Our Drill Hall (now the Trans Canada Fitness Center) was constructed in 1902. Men from this area had served in the Anglo-Boer War and they became the core of our local militia – D Company, 102nd Regiment, Rocky Mountain Rangers. Many young men were attracted to this way of life and joined the local militia. It was considered a proud duty to have served in battle in South Africa for the glory of the British Empire.

The young men of the day were heavily influenced by the literature of the time which portrayed the Boer War of 1899 and war in general as a glorious enterprise without much loss of life. It took the slaughter of the coming war to reduce the appeal of glory and adulation and adventure for these young men.

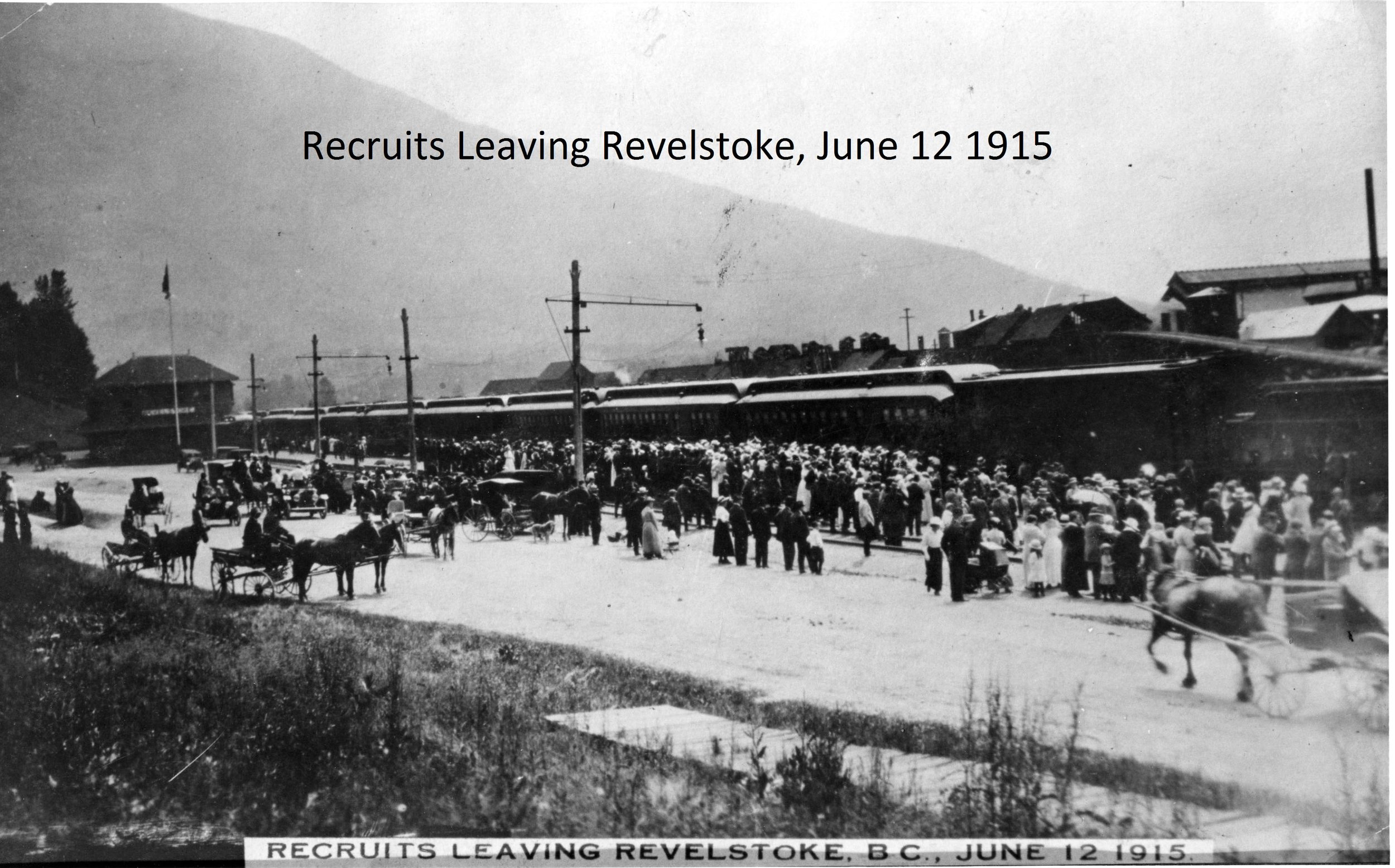

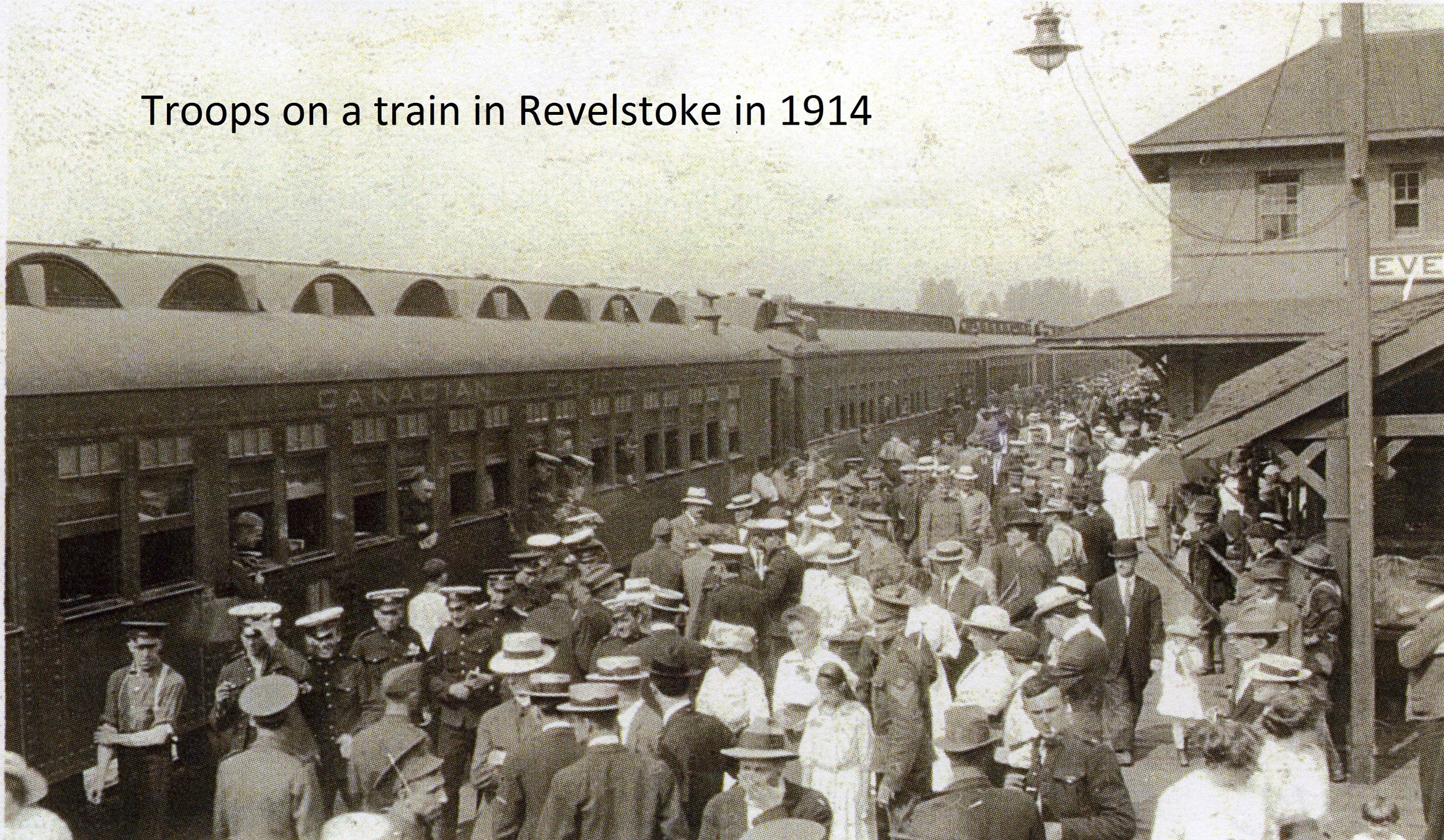

So at the beginning of the war in August 1914 these were the men, (or “boys” as they were referred to), who were the first to answer the call of the Empire. Some 69 men from our city immediately signed up as volunteers. About 30 of them were chosen for what became known as the First Contingent. Around the end of August they passed through Revelstoke after some initial training at Kamloops. The passage of our “boys” through Revelstoke was, quite naturally, a significant event in Revelstoke’s history. The newspaper of the day carried it this way:

“Hearty Farewell to Revelstoke Volunteers”

“One of the most striking demonstrations ever seen in Revelstoke took place at the Canadian Pacific railway station on Sunday (August 30, 1914) when the citizens bade farewell to a contingent of volunteers from the city of Revelstoke who passed through on the midday train from Kamloops on their way to Valcartier. The station was thronged and the troops were given the heartiest and most enthusiastic sendoff.”

On the grounds of the Revelstoke Hotel (on the hill above the CPR station) children from the two public schools and students from the High School were massed. It was an ideal situation for the purpose and the children, the girls in light summer dresses on one side and the boys in a body on the other, presented an effective picture as they saluted the arrival of the train with hearty cheers and the waving of many flags. The children then marched to the station headed by the G. Verdi band. The City band was also on the scene and, along with the civic guard carrying two large Union Jacks and the flags of the allies, marched to the station and took up a position behind the children.

The station was thronged and the music of the bands, the singing of patriotic songs, cheering and waving of flags by the children, with the roar of welcome from the crowd on the platform made a scene of animation which will long be remembered by all who witnessed it.

The Revelstoke volunteers appeared to be in the best of health and spirits. They disembarked from the train and marched in front of the children and gave hearty cheers for Revelstoke. Each man was presented by the Women’s Relief Society with a case containing socks, darning cotton and other requisites and a box of apples was placed on the car. Many flowers and other gifts were made to the soldiers. On Monday a similar demonstration occurred when another party of Revelstoke volunteers passed through the city on their way east.”

The meeting of the trains carrying our volunteer soldiers was an important feature of community life in Revelstoke during the war. At all hours of the day and night citizens would make their way up to the train station, and offer support to the soldiers. As mentioned in the newspaper article that I read, Relief Societies had been formed immediately upon the commencement of the war. A Patriotic Fund to financially support the families of the soldiers was established. The Women’s Relief Society eventually evolved into the Revelstoke Red Cross Society.

A High School Girls Patriotic Society was formed under the guidance of Miss Annie Eaton, who joined the High School staff in 1915 and taught there until 1922. She was an older sister to Judd Eaton, one of those six young men who perished on June 3, 1916. The High School girls assembled Christmas parcels, knitted socks and sent letters to the former High School boys serving at the front. The museum has in its archives the record of their meeting minutes from the High School. A High School Boys Cadet Corps was also formed.

The Red Cross became one of the two foremost organizations supporting the war effort in Revelstoke. Our local Red Cross Society sent off literally tens of thousands of socks, bandages, and other items to the war front. They conducted many fund raising drives and always commented positively on the generosity of spirit and money on the part of the citizens of Revelstoke. Every week, it seemed, there was an article in the newspaper listing all their contributions and their supporters. They were consistently supportive of the war effort to its very end and beyond. (A long-serving secretary was Mrs. Florence Soames, who sacrificed a son, George Soames, to the war.)

The other organization was the Women’s Canadian Club, as the former Revelstoke Canadian Club was known back then. They were instrumental in bringing to Revelstoke (by train of course) world-famous speakers and personalities such as Nellie McClung, a Canadian suffragette trying to bring the right to vote for the women of Canada. One of her arguments for women to be granted the right to vote was that they were also making great sacrifices for the war effort and should be considered equal partners with men. Indeed in the B.C. Provincial election of 1916 referendums were passed by the male British subject voters of B.C. in favour of the Prohibition of alcohol and for the right of women to vote. And in the Federal election in December of 1917 the wives, mothers and sisters of the soldiers serving overseas were given the vote.

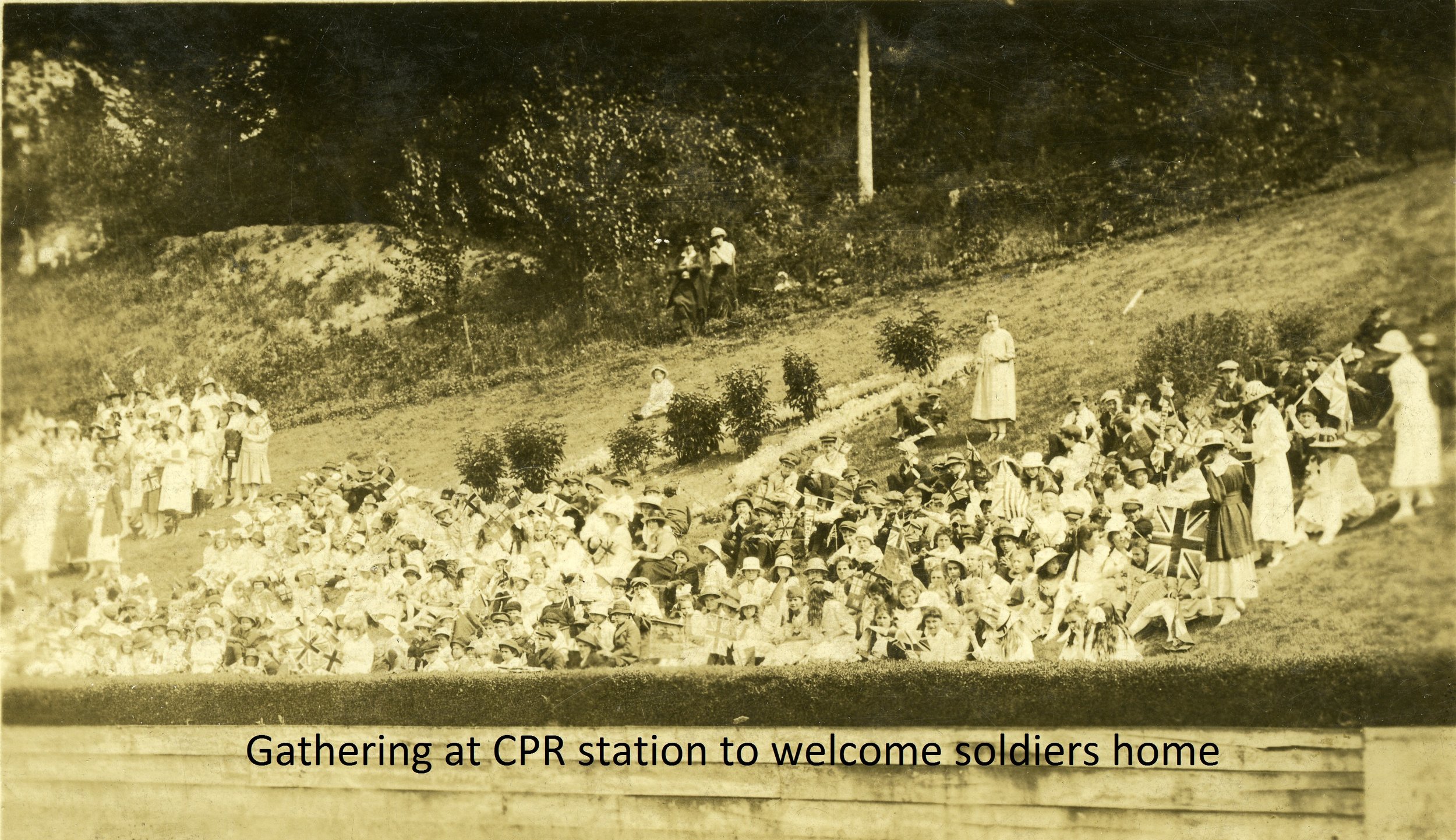

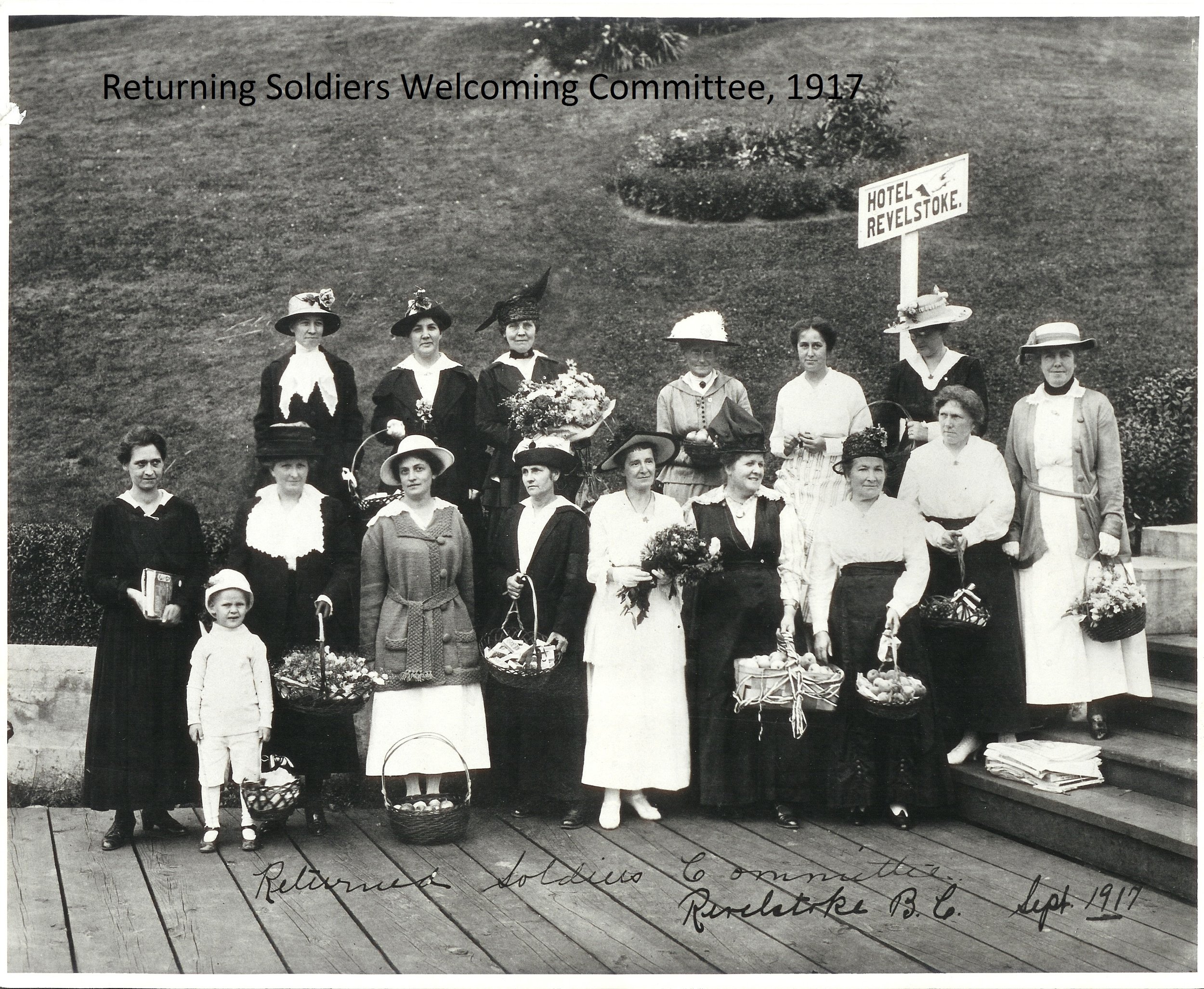

The Women’s Canadian Club also did numerous activities to support the war effort. In October or November they would organize a Christmas Hamper Campaign to fill and send off Christmas packages to our Revelstoke Boys at the front. A tea would be held at the home of a prominent woman and the women of Revelstoke would drop in, make their contribution, and be offered refreshment and entertainment. This was always hugely successful. Another activity they did was to meet the passenger trains and sell flowers to the travelers – all contributions going to the war effort. At the same time they would be promoting the tourist values of our fair city. Another, sadder, duty they performed was to meet the trains that carried our returning, wounded soldiers. They were among the first in Canada to do this and their compassion was much appreciated by the men. They would hand out items such as sweets, apples, tobacco etc. and try to lift up the spirits of the soldiers. They were instrumental in the construction of the World War One Memorial Plaque placed on the Courthouse, and for the planting of maple trees around the Courthouse in honour of the local soldiers. This city took pride in all its efforts to support the war and worked hard “doing its bit.”

Another organization that was very important to community life during the war was the Christian churches. Back in 1914 almost everyone in town was either Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist or Baptist. Sometimes the local newspaper printed their ministers’ sermons. When war started the churches were called upon for their support and they did not waver. In January of 1915 the churches were asked to conduct prayers for Peace and Victory. The ministers’ messages were all printed in the paper. Reading these gives one a flavour for the enthusiasm and determination and commitment to the war effort of the people of Revelstoke. It also gave me an important insight into what the ministers, and most likely their congregations, believed were the reasons they were fighting this war. At one point during the war the local ministers were asked to preach recruiting sermons by the Board of Trade, the precursor to our Chamber of Commerce. These also were printed in the paper. These messages consisted primarily of appeals to duty, responsibility, commitment, patriotism and the crusade against evil in the world, identified as German militarism. The churches, along with other organizations such as the YMCA and the Fire Brigades, constructed Honour Rolls listing all the volunteers from their denomination or organization who had joined up for the war effort.

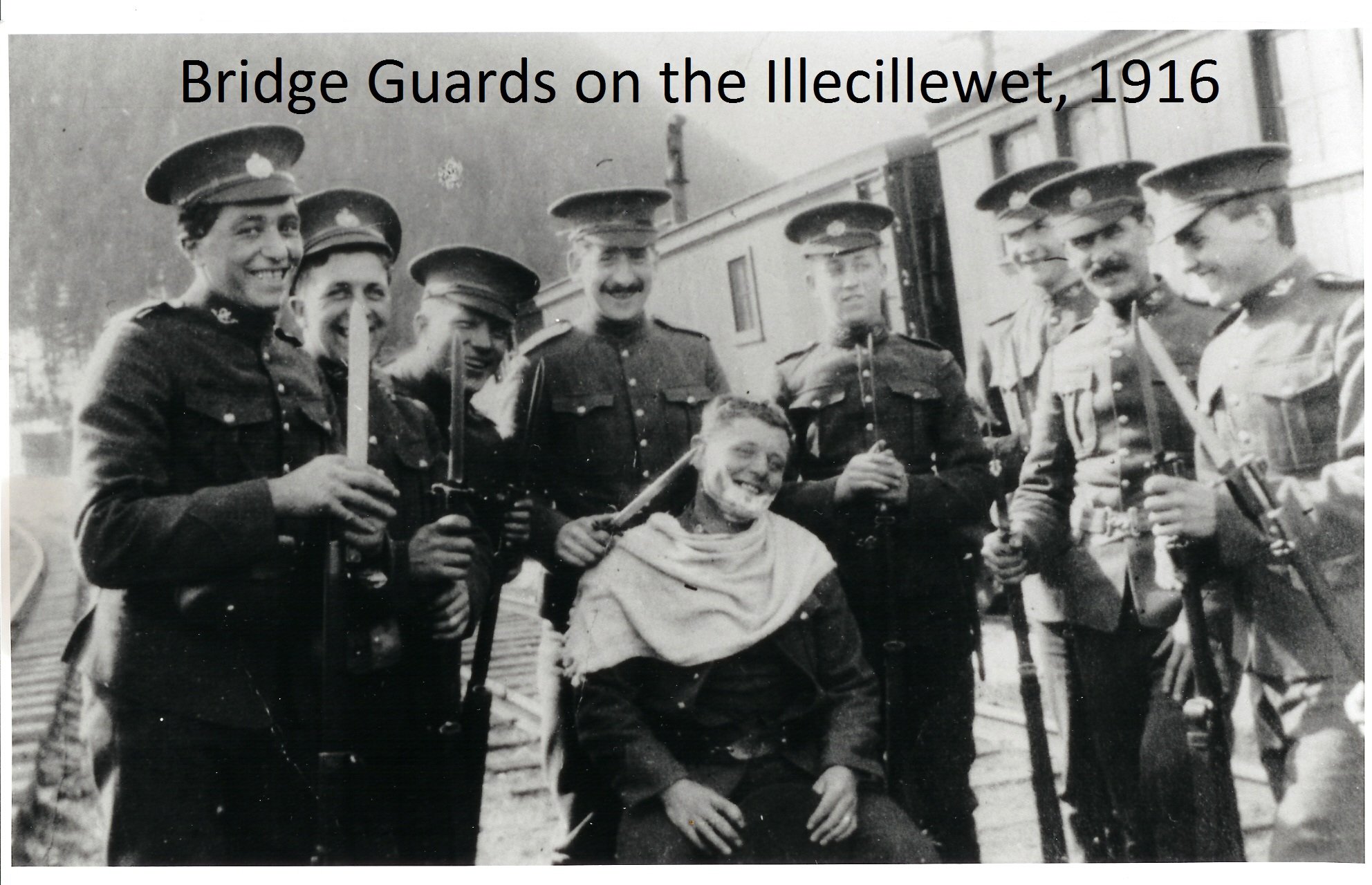

Let us now return to the Fall of 1914. Those men not needed for the First Contingent were either put to duty guarding the CPR rail bridges, or practicing their marksmanship and drilling at the Drill Hall. The rest of the city was very busy socially, as it was for most of the first three years of the war, entertaining our volunteer soldiers, holding dances, picnics, church gatherings, sporting events and other social activities. The paper also carried entertaining accounts of house parties and sleigh rides out to Greely Creek.

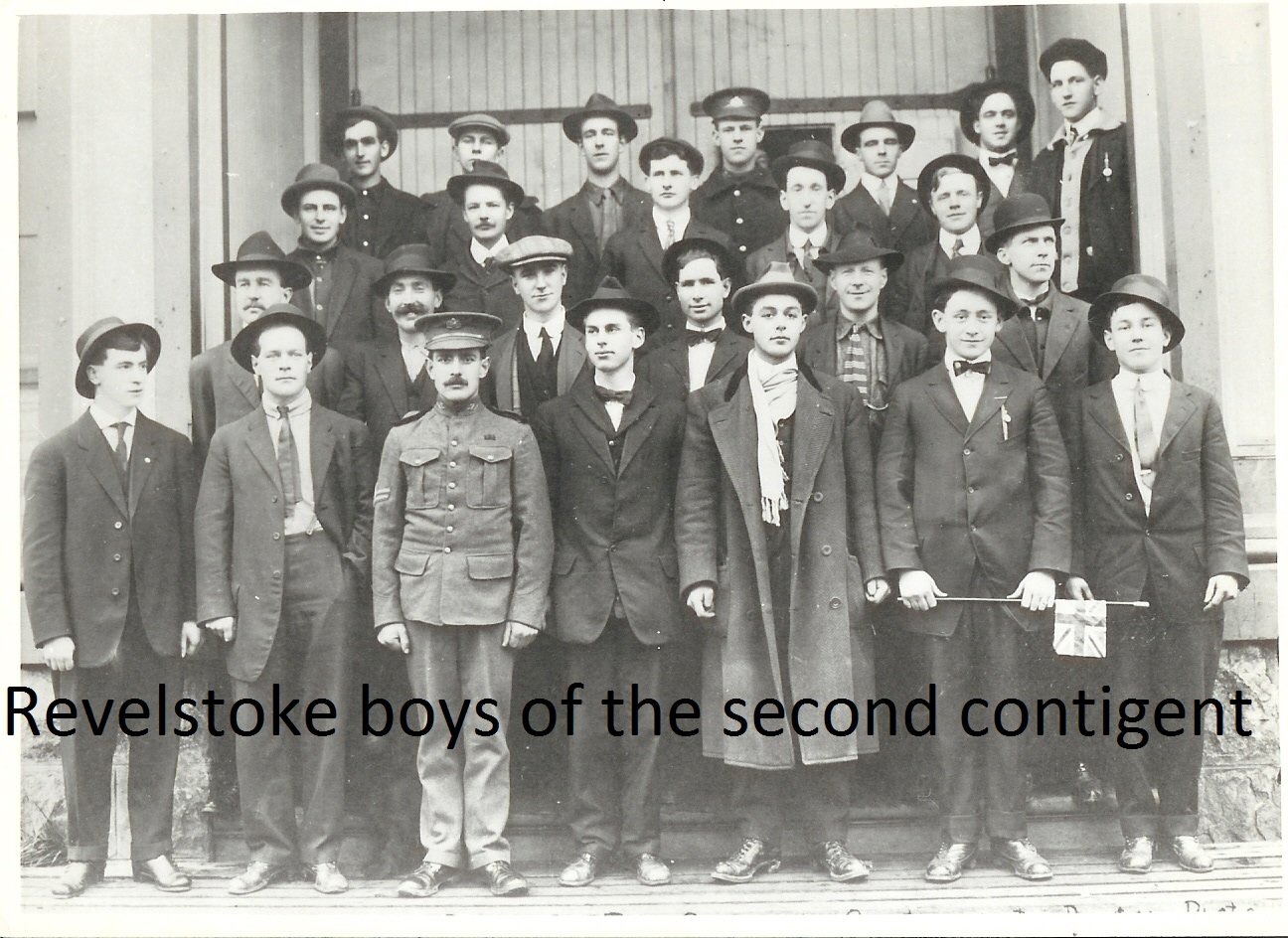

A Second Contingent of volunteers was quickly called, and in November 1914, they marched in a body from the Drill Hall and boarded a train for Victoria where they trained over the winter. An interesting letter from the camp in Victoria printed in the paper noted that some of the boys had met up with some Revelstoke girls at the local skating rink and enjoyed an afternoon of skating. In the meantime the First Contingent had sailed from Valcartier, Quebec and were now encamped on the Salisbury plain in England where they endured horrendous living conditions in the damp English winter. The Second Contingent sailed over to England in the early spring of 1915 and joined the First. Many letters were received from the men describing their adventures with mostly good humour. The train rides across the country were inspiring experiences for our volunteer soldiers and were an important bonding experience toward identifying themselves as Canadians rather than British (more than 75% of the earliest volunteers had been born in Britain and were recent immigrants). They were greeted enthusiastically by the Canadian people everywhere they went. But things were about to change in the spring of 1915.

In April of 1915 the Canadian Corps endured its baptism of fire. They had been placed in the Ypres salient on the Western Front in Belgium when shortly after their arrival the German army attacked using a new weapon of war. In addition to the usual killing instruments of artillery, machine gun and rifle shot, the German commanders tried an experiment using chlorine gas for the first time in modern warfare. Despite tremendous losses the Canadians managed to hold the front. Revelstoke suffered its first casualties of the war, Walter Robinson and John Boyle, two men who had very close ties to our community. John Boyle was the son of a local baker and the brother of Allan Boyle who later became a long-serving alderman of this city in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Allan Boyle’s son became an Admiral in the Canadian Navy. John Boyle was only 17 or 18 years old when he was killed. His body was never found or identified and his name is memorialized on the Ypres ( Menin Gate) Memorial in France. Walter Robinson had a brother, Arthur Robinson, who perished later in the war. Both Robinson brothers were born in Revelstoke in the 1890’s. This was the only brother combination from Revelstoke to die in the war. Numerous other brother combinations served but they managed to survive. The Robinsons were early forestry pioneers in Revelstoke.

As can be imagined these deaths had quite an impact upon the city and there were numerous articles about them. Also at this time letters began reaching home describing in graphic detail the fighting the men had endured. Some of these were printed in the paper. I was extremely surprised to read such graphic descriptions of the violence and suffering the men had endured. My guess is that the authorities thought these letters were too graphic also because I never saw another letter in the newspaper again with such detail. The letters toward the end of the war were mostly travelogues with humorous descriptions of life at the front.

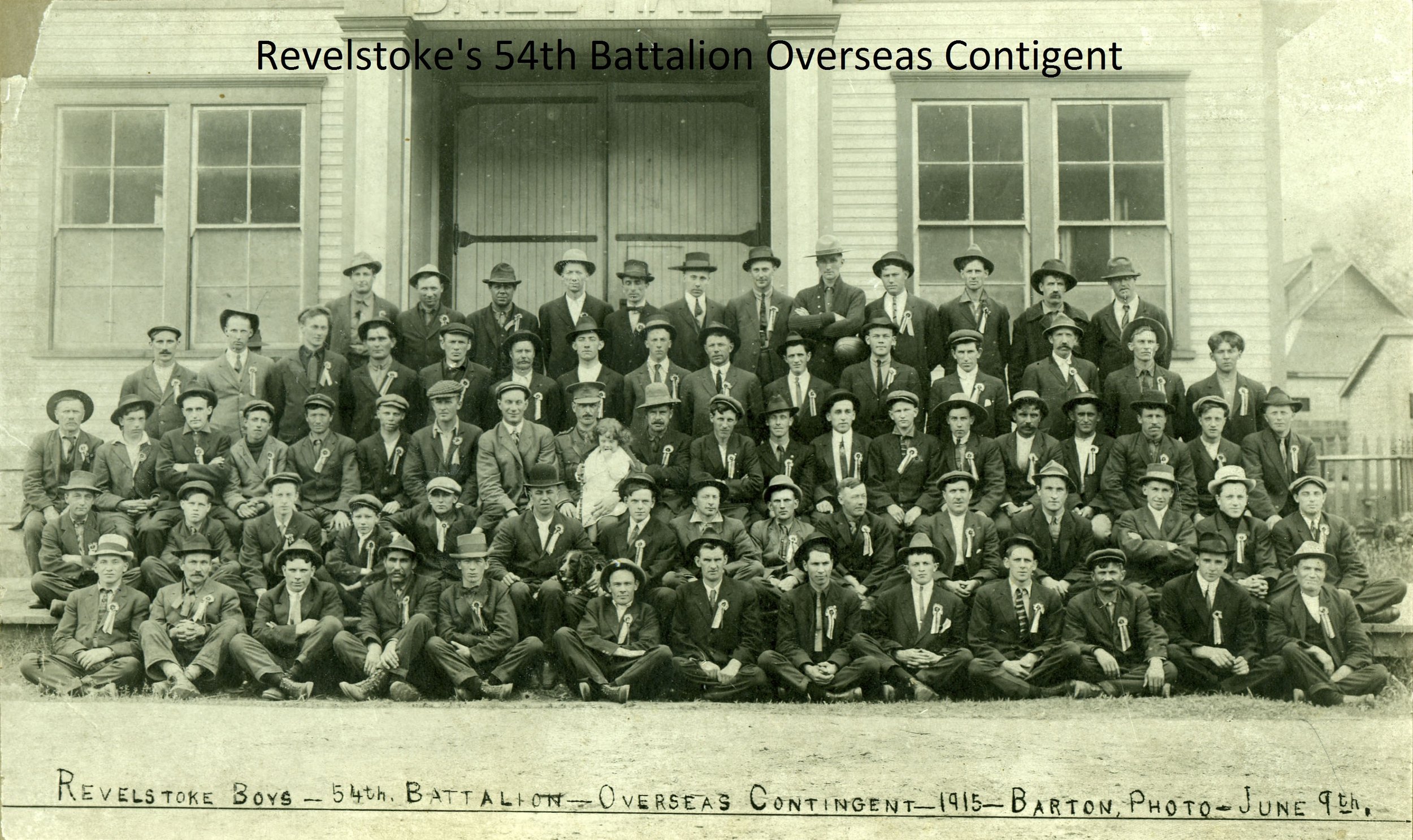

In the spring and summer of 1915 Canada stepped up its recruitment of soldiers. Perhaps the most famous local regiment of the war came into being at this time. The 54th Kootenay Battalion was readied to receive the men of the Kootenay and Kamloops area. By the summer of 1915 some 100 men from this area alone were training in Vernon. These were exciting times in the city with numerous patriotic receptions and events put on to encourage and support our volunteer soldiers.

One such event was a reception held at the Lindmark home at 706 Mackenzie Ave. At the Lindmark home there was at that time a balcony around the second floor and from there speeches were given and underneath the balcony the city band played patriotic songs and popular tunes of the day. The citizens wandered about the magnificent lawns and gardens encouraging the new recruits.

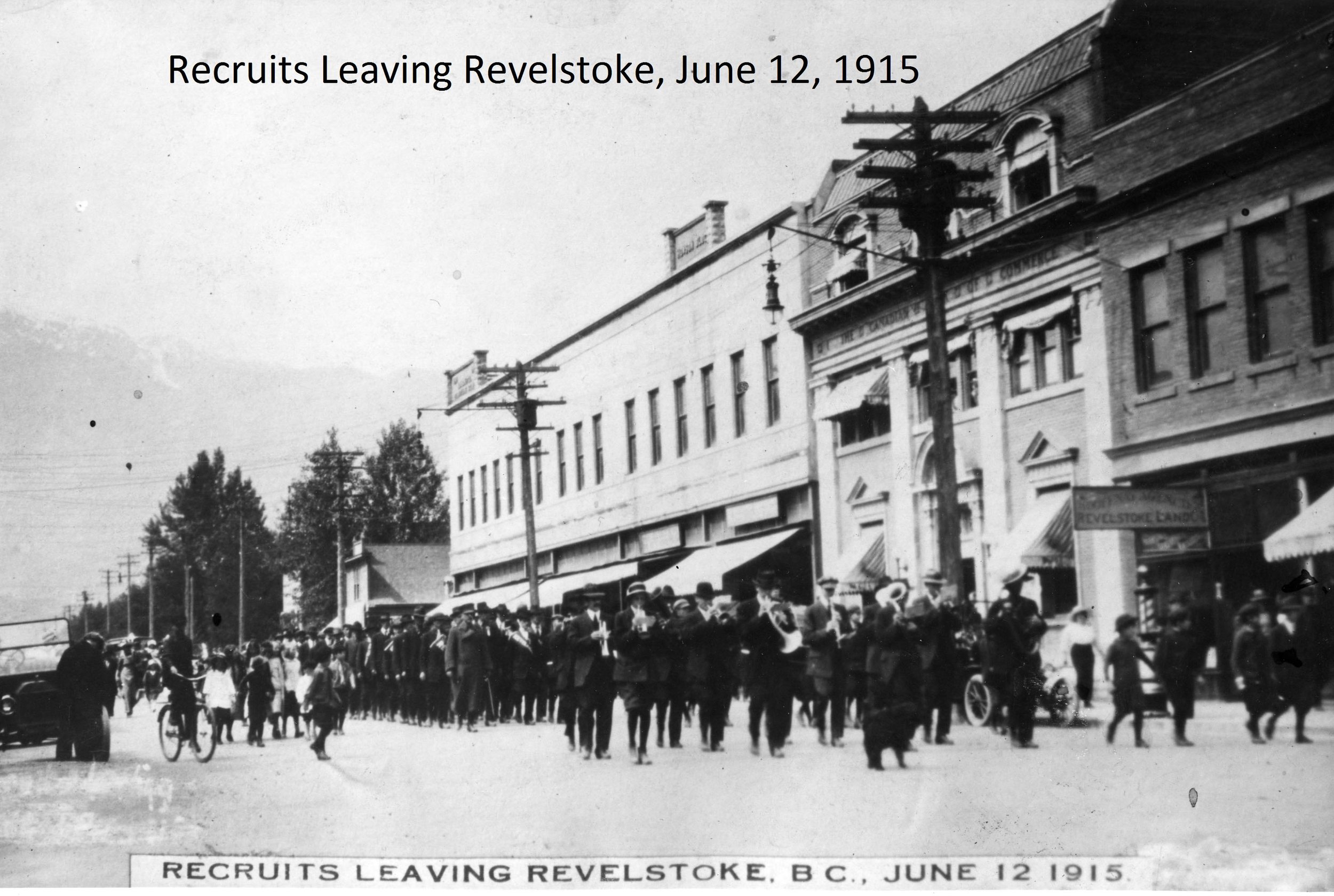

In addition to these events patriotic parades and speeches were the order of the day. One such event was held on the evening of June 3, 1915. A parade began at 7 o’clock through the streets of the city. It was headed by the Mayor and the city band, followed by the bugle band of the 102nd Regiment, the High School cadets, 54 recruits wearing the rosettes furnished by the Ladies of the Red Cross Society, the Boy Scouts, and many citizens in automobiles. The parade eventually arrived at the Drill Hall. As the newspaper of the day put it, “The streets in front of the hall were blocked by one of the biggest and most loyal and enthusiastic audiences ever assembled in this city.” The program consisted of speeches by a number of prominent men (including clergy), solos by local artists and music by the city band. The newspaper described the speeches this way.

“The keynote of the speakers’ remarks showed that the paths of duty lead to the recruiting office; Great Britain is fighting for freedom and liberty against the aristocracy of German militarism; that the 54th Battalion must go forward with courage to fight for the independence of the civilized world and the independence of those who follow after them, and take their place besides those who have so nobly upheld the best traditions of Canada and the British Empire in the fighting line in France.”

A more succinct summary of why Canada fought in World War One I have not found anywhere. These speakers felt that Canada and the British Empire were fighting for a “great” purpose and cause. This belief sustained them through the dark days of war still to come. As the Anglican minister, C.A. Procunier put it, “It is a great honour and privilege to be born under the Union Jack. Upon all true patriots lay the greatest responsibility that ever befell citizens of the Empire. The Empire needed men. Are the men before me between the ages of 18 and 45 to prove themselves patriots or cowards? Our King and Country need us. The Empire is fighting with its back to the wall as never before. It is a serious hour. Our young men will respond to the call because it is right to do so. They would be fighting on the side of right. It is their duty to enlist. They should respond to the call because they are lovers of liberty and freedom. God is on the side of right, truth, freedom and liberty. It is our duty not only to supply soldiers and munitions, but also to pray to God to sweep away the curse from the world, to establish liberty, and to serve God with freedom.” Rev. Procunier later went to France to serve as a chaplain; his son joined up and unfortunately became a prisoner of war. When word trickled back that some Revelstoke men were prisoners of war the citizens of our town became strong supporters of a campaign to help our POW’s through the Red Cross package program.

Despite the exhortations of Rev. Procunier (and many others), recruitment began to flag in 1916. It became more difficult to sign up replacements for all the battle losses. Talk of Conscription began to be heard from our politicians and military leaders. It is only at this time that any signs of discontent or dissent reach the newspaper pages. We still have to do much reading between the lines to find much of this. Throughout the war years our local paper, the Review, remained staunchly in favour of a vigorous prosecution of the war. The Review, being a staunch Liberal newspaper, did have a problem with the Conscription issue. At the time Conscription became an issue in Canada, the Federal Liberal party was led by Sir Wilfred Laurier. The Liberal party had a strong base of support in Quebec and Quebec was opposed to Conscription. The Liberals (and the Review) tried hard to straddle this issue which threatened to split the party and the country. French Canadians, on the whole, had no desire to fight in Britain’s wars of imperialism and had little love for France, who they felt had abandoned them when Britain conquered Quebec.

Nevertheless in early 1917 Conscription became the law of the land. There was a Federal election in December 1917 in which the ruling Conservatives were returned to power, including the MP from our riding. An interesting note for Revelstoke is that the candidate who was running on an anti-conscription platform garnered about 15% of the vote and the Liberal candidate about 30%. From the election results one could deduce that there was a significant minority of English Canadians unhappy with conscription and perhaps willing to be receptive to peace talks to end the war. I must say that when I was slogging my way through the 1917 issues of the newspapers I was getting a bit war-weary myself. It was getting to be depressing reading. I could begin to imagine how weary the people of Revelstoke must have been. Will this war never end?

In the Museum we have a copy of the Howson family history. They were early merchants and funeral undertakers in Revelstoke. The Howson block across from City Hall and the Howson home, the Birches, at 815 Mackenzie Avenue were built by them. In this family history there is a reflection on what life was like here in the latter part of the war. Apparently it was the practice of young people before the war to sometimes “borrow” the small organ from the Scandinavian Church on a Saturday evening and wheel it up Mackenzie Avenue and knock on a door and ask to be let in to party. The occupants would get up, there would be much singing and dancing and joviality. After the party was over the “borrowed” organ would be returned in time for the Sunday Service. Mrs. Howson recalls how much she resented having to get up and entertain these young people. Later on in the war she missed these parties because it was a reminder to her that there were very few young men left in town. In her view life was getting drearier and more depressing. She recalls the tramp of the marching feet of the soldiers who had disembarked from the troop trains and marched up Mackenzie Avenue where they turned around in front of her house and returned to the train station. She would find herself thinking how many of these men were destined to become cannon fodder for the German guns.

In the spring of 1918, at the time of the last great German offensive of the war, a note of desperation begins to creep into the newspaper. Rationing is introduced, people are exhorted to use their food more efficiently, more vegetables need to be planted and harvested for the soldiers at the front and more bonds need to be bought to finance the war. Finally the Allied armies regain the upper hand over the German forces and Armistice is declared on November 11, 1918.

Emotions in Revelstoke on that day were mixed. There was joy of course but on this day it was mingled with sadness. On November 10, 1918 Allan Daniel McDonald, a recently returned soldier working on the railway, succumbed to what was euphemistically called “trench fever.” This was probably another term for a lung disease that he had developed from living in the trench conditions at the front. His funeral was held on November 11, 1918 at the Catholic Church. After the funeral his body was to be transported to the train depot for return to his family in eastern Canada. The City delayed the beginning of the end of war celebration in order to allow the funeral procession to wind its way down Mackenzie Avenue and across the railway crossing. Then the victory parade could start.

Peace had come to Canada and to Revelstoke. The war to end all wars had run its course. Some 100 men from the Revelstoke area had paid the supreme sacrifice. They had answered the call and now most lay buried in Europe. Who knew that twenty years later the sons of these men would once again be called to serve their country in another World War.