Black History Month

Black History Month is celebrated in Canada every February. Canadians are invited to participate in festivities, events, and learning opportunities that honour the legacy of Black Canadians, past and present.

We have not participated in Black History Month at Revelstoke Museum and Archives in the past. It is too easy to say that Revelstoke never had a significant presence of Black citizens, and therefore there is nothing here to talk about. However, we have learned that sometimes the stories lie beneath what is easily accessible. Why weren’t there many Black people in Revelstoke? If they came here, why didn’t they stay and establish their lives here?

We don’t think of historic Revelstoke as a diverse community, but that isn’t entirely true. According to the 1901 Canadian Census, about 6% of the population was Chinese. There were also many Japanese people living and working in and around Revelstoke, along with South Asians. Their stories rarely made it into the pages of the local newspaper unless there were negative interactions with the White population, or unless they were considered integrated and accepted into local society.

The history of Black people in Canada is long and complicated. Slavery in Canada was abolished in 1833, and many fleeing slaves were able to find refuge in this country, but that doesn’t mean that they were always welcomed, or that their lives were easy. Black settlers who tried to make a life in British Columbia in the 1850s and onward faced severe prejudice, as did settlers from other non-Caucasian races.

The 1901 census lists one Black woman working in Revelstoke as a prostitute. Her name was Edith Campbell, and she was born in the United States in 1880, making her 21 years old. She was listed as divorced, and as Irish, meaning she was likely biracial or multiracial. A man named Albert Moss was living in Comaplix, a sawmill town on the Northeast Arm of the Upper Arrow Lake in 1901. He was born in the United States in 1841, making him 59 years old. He had been in Canada since 1879 and was working as a barber. How do we know they were Black? We know because the 1901 census included a column for skin colour. B indicated a Black person, W indicated a White person, Y was for East Asians, and R for Indigenous people. Remember, this was in an official document of the government of Canada.

A Black woman named Alice Foster lived in Revelstoke from 1885 to 1888. She and her husband had been following railway construction across Canada until her husband, a barber, was killed by a client at Golden. Alice Foster continued on to the newly established railway construction town of Farwell, where it is believed that she opened a brothel. She moved to Nelson in 1888 where she established a laundry and was known as “The Midnight Nurse,” due to her work as a midwife. She died in Nelson in 1894. There were possibly other Black men and women in Revelstoke in the early days of railway construction, but their stories have not been recorded.

The infrequent references to Black people in early newspapers were racist, without exception. Derogatory terms were used to describe them, and they were always portrayed in a negative light. Even local government documents, including police report books used slang derogatory terms to describe their interactions with Black people.

An entry in the record book of the Revelstoke City Police in July of 1908 reports the theft of a watch. The victim of the theft had been drinking heavily, and when reporting his missing watch, indicated that he last remembered being in the company of a Black man, although a racist term was used in the official report. The police then rounded up five Black men who were in town. The watch was not found, but all five men were ordered to leave town immediately.

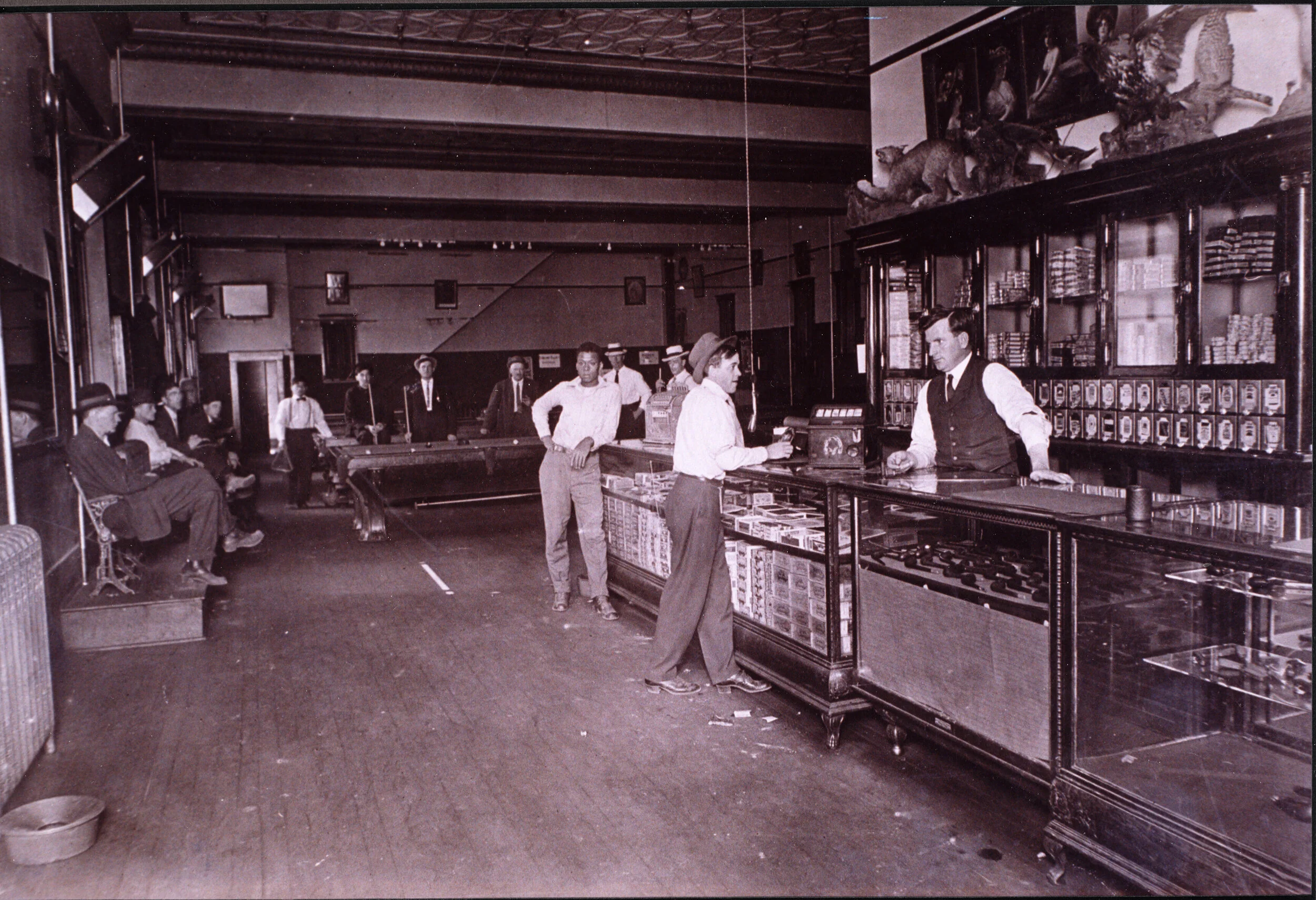

The museum collection includes several photographs showing people with blackface makeup. This was often a common part of a costume at masquerade balls. Even the Armistice parade on November 11, 1918 included an oxen-drawn cart with two local men in blackface. A very racist float with people in full black body paint was part of the 1958 Golden Spike Days parade. What our collection does not include is Black people living and working in Revelstoke. The one photograph that we do have includes an unnamed Black man in the McKinnon’s Cigar Store and Pool Hall, where he was likely running a shoe-shine stand.

Just as with Asian immigrants, Black people were limited in the jobs that they could hold. Although some racialized people were able to go into business for themselves, the majority of them were in service jobs. It was considered acceptable for Black and Asian people to work as barbers, cooks, servants, gardeners, and labourers. Women had even fewer options than men.

An incident was reported in the local newspaper in 1903, regarding a near lynching at Ferguson, a mining town near Trout Lake. A Black man had angered some of the local citizens who decided to take justice into their own hands. The man, who was never named, managed to flee. The article was written in a light-hearted manner, and excused the actions of the men who tried to lynch the Black man. The language used was extremely racist, but was not unusual for the newspapers of the time.

I believe that the above incidents answered the question of why so few Black people came here, and why they did not settle here. It was not a welcoming or safe place for them.

Why is this relevant to us now? We like to think of Canada as welcoming, and less overtly racist than the United States. It is important for us to acknowledge the racist, colonialist, and misogynistic history that has allowed systemic racism to be ingrained into our culture. It is important that we hear and acknowledge the stories of Black, Indigenous, and Asian people who tell us their experiences. It is not enough just to claim that we are not racist. We must be actively anti-racist. When people cry out in anguish, “Black Lives Matter,” it is up to us to echo that, and to stand in solidarity with them. The next time someone responds to “Black Lives Matter” with “All Lives Matter,” ask them to prove it. How is society showing that Black lives matter as much as White lives? What structures are in place to ensure that everyone has equal access to services, and that every culture and perspective is included and represented in an equal way? The well-known American anti-racism activist Jane Elliott once asked a largely White audience to stand up if they wished that they could be a Black person in America. No-one stood. Elliott pointed out that everyone in that audience recognized that Black people experienced barriers that they, as White people, did not.

This year, we are acknowledging Black History Month in Canada at the museum, and acknowledging that there is much that we don’t know. We don’t have the stories from the perspective of Black people who did come here, and who tried to make Revelstoke their home. At the very least, we can start a dialog about racism, and do all that we can to make sure that Revelstoke is a safe and welcoming community for everyone.

Inside McKinnon’s Pool Hall, circa 1915. Hector McKinnon is behind the counter, and the other men are unidentified.